Struggling with the return to office life? Suffering from the burnout blues? Esquire Japan’s man in Tokyo, Christopher Berry, shares his take on the most relinquished and misused part of the typical Japanese working day. Despite Gordon Gekko’s claim, lunch is definitely not for wimps.

No one really knows what is going on in Tokyo. It is an onion infinitely unpeeling itself. Buildings are constructed and demolished, companies boom and bust, brands come and go, all within days. In the time it takes one to survey each of Tokyo’s 23 wards, the ward one started in will have again evolved past the point of recognition. Most office workers here are overworked. Ask a Tokyoite what they think amidst it all, and most likely they will blink their eyes and follow up with an expression of token assent. Most people here remain siloed within the quotidian routines of their life, and I can’t blame them. Tokyoites are far from alone in feeling disconnected from the rapid changes taking place at home and abroad.

But whether foreigner or Japanese, what we as Tokyoites are most dialed into is our work. Japanese society values the collective over the individual, and company culture in Tokyo is unsurprisingly among the most rigorous on the planet. But this desire to exceed expectations at all costs has left many cracking under the pressure. In recent times, incidents of extreme burnout at some of Japan’s largest corporations have begun to change all that, with office computer connections and lights shutting off automatically at designated times.

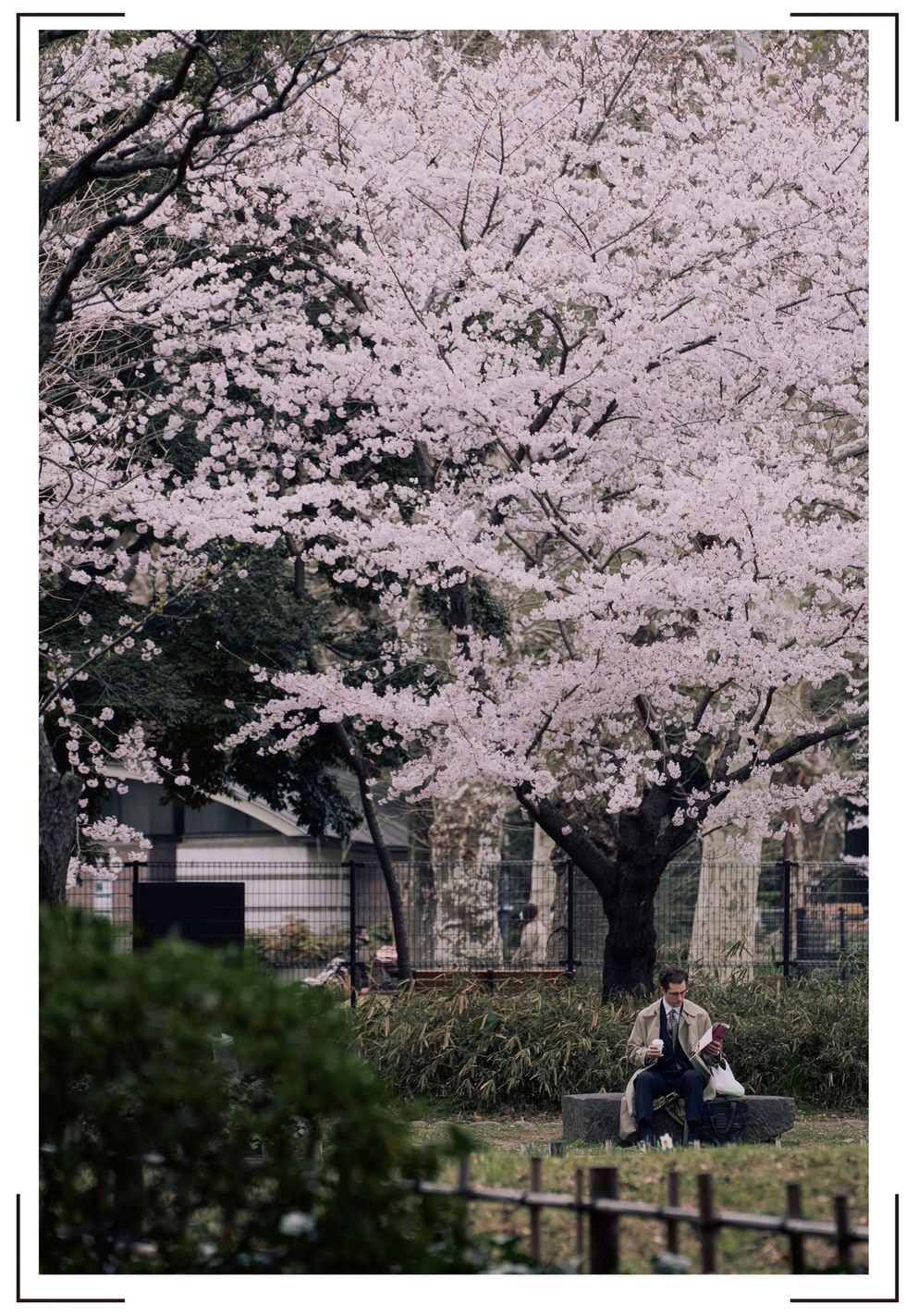

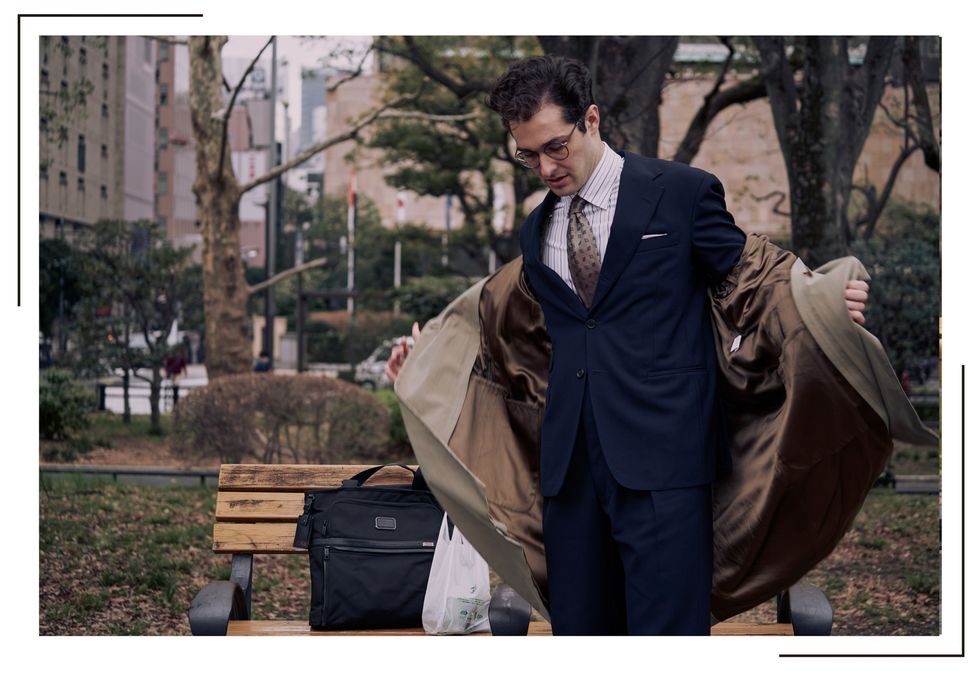

It is essential now more than ever that over-taxed office-goers make time to recharge their batteries and convene with nature’s vibrations. But how and where does one even do that in Tokyo? The answer lies in taking back the long-overlooked lunch break.

If you observe a typical office in Tokyo, even at progressive and forward-thinking firms, employees often forgo a proper lunch break, eating in the office cafeteria or joylessly shoveling food into their mouths while they work. This I find to be a critical error.

The definition of a “break” is to completely disconnect and remove one’s self from their work. I’d encourage everyone reading this to take those words more seriously, go outside and even just find a nice bench to sit in the sun for a few minutes. The renewed sense of focus and clarity will pay dividends when you get back to work. I promise you.

There really are no excuses for lunchtime self-neglect. We are blessed that the green spaces in Tokyo are abundant. According to Tokyo’s Bureau of Construction, Tokyo contains 8, 287 urban parks and over 3,000 more if you count the suburban outskirts. That’s enough for roughly 5. 73 square meters of park for each of Tokyo’s nearly 13.96 million residents. By contrast, my hometown, New York, has roughly 1, 700 urban parks across all 5 boroughs for its 8.5 million residents.

At once exquisitely manicured works of art, and valuable pieces of real estate with rich histories that can be felt as soon as one enters.

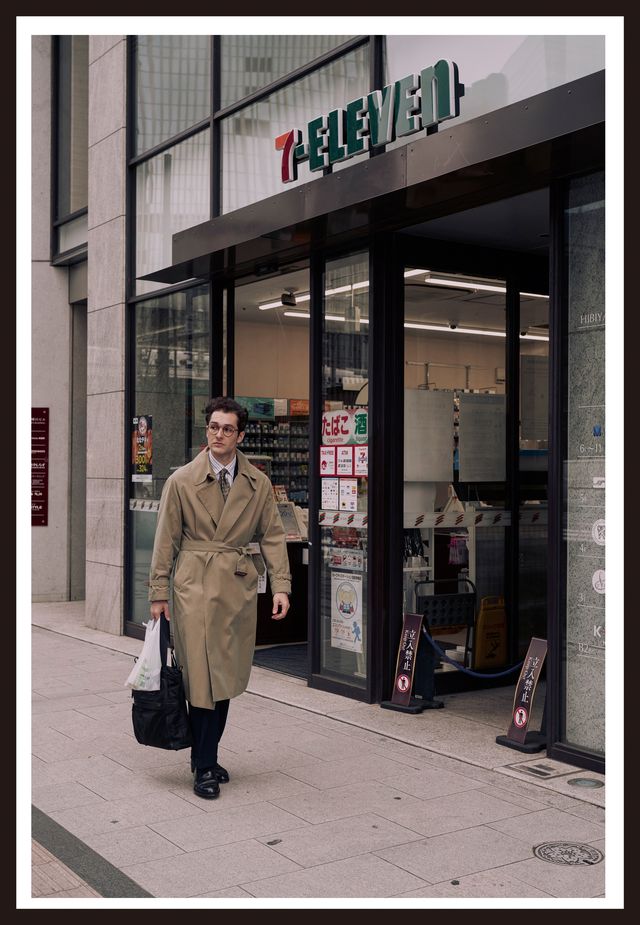

A park setting can transform even a ¥300 umeboshi onigiri and mugi cha (that’s a pickled plum rice ball and buckwheat tea) from “7-Eleven” into a moment of meditation. Though far from the monastic practice of za-zen meditation, allowing yourself this time to let your mind wander in plain air, is a welcome second-best choice.

Just take a page from the book, “On the Principles of Zazen,” written by philosopher and Soto Zen School founder, Dogen. A Kyoto native dissatisfied with his level of schooling, he travelled to China for 5 years to learn Buddhism from what he viewed as its source. When he returned, he brought the practice of sitting meditation to Japan with his treatises, entitled the Shobogenzo. In it are 95 essays with detailed instructions on how to find exactly the right tatami mat and environmental conditions to engage in properly seated meditation, or za-zen. While most of the physical parameters he outlines are tricky to achieve in a public park, his definition of the proper mental state for meditation is remarkably apt:

“In zazen, all involvements must be cast aside, and all affairs put to rest. It is not thinking good, and not thinking bad. It is not consciousness, and it is not contemplation…

… Sitting in meditation silently and immobile, thinking of not thinking. What is thinking of not thinking? Non-thinking. This in itself is the art of za-zen. Zazen is not learning Zen. It is the Dharma-gate of great repose and bliss, undefiled practice realization.”

Dogen’s words in 1243 from a port town in Fukui prefecture, are today equally at home in Tokyo or anywhere else. While their truth may seem like a riddle (a zen Koan if you prefer), I think we could all benefit from a few minutes of non-thinking in our daily lives. Don’t you?

Below is a list of some notable parks, Buddhist Temples, and Shinto Shrines near Tokyo’s busier financial districts that I recommend for visitation.

- Hibiya ParkMAP

- Yoyogi ParkMAP

- Koishikawa KourakuenMAP

- Zojo-ji TempleMAP

- Meiji Jingu ShrineMAP

- Togo ShrineMAP

According to the Agency of Cultural Affairs in 2013, in Tokyo, there are 2,872 registered Buddhist temples and 3,008 Shinto Shrines distributed throughout its 23 wards. Entering one of these facilities for the first time can be both awe-inspiring and intimidating, transporting visitors beyond the incandescent hum of Tokyo’s streets. Making proper use of a Shinto Shrine or Buddhist temple is its own reward, enhancing your experience of the space while showing your fellow Tokyoites that you mean business, even on a lunch break.

When you come across a Buddhist Temple or Shinto Shrine, you’ll be confronted by a red wooden archway, or gate (sanmon at Buddhist Temples, torii at Shinto Shrines). Before entering, clap your hands once in front of your chest and simultaneously bow as deeply as you can (ideally 90 degrees). There is a tradition for men to enter with their left foot first and women with their right foot, however I find that most do not remember or observe this outside of formal ceremonies today. Do not enter directly in the center of the gate, as that is considered holy ground where the Gods are said to pass through.

You will then be greeted by a running water vessel, called a temizuya, intended to cleanse the body and spirit before proceeding to the main building. After cleansing your left and then right hands, pour some water into your cupped left hand to rinse your mouth. Never drink directly from the ladle and once finished rinsing, cover your mouth to spit the water into your left hand (away from the basin), then re-rinse the left hand with the ladle. Hold the ladle with the bowl face down and the handle pointed downward away from yourself to empty it, then return it to its original place.

Once past the entrance, you should walk to the main building or Hondo, which houses a central altarpiece, featuring a representation of the local deity for which this shrine was originally built. As Shinto is an animistic tradition, Shrines can be dedicated to an infinite array of deities and animalistic spirits which are said to imbue all living and inanimate things.

Nearby there is a box with open slats into which you may gently place your monetary offering. Avoid noisily throwing in pocket change like it’s a fountain at Central Park, as you are in the residence of Gods at this point. If there is a bell or gong, ring it 2-3 times, bow twice deeply, clap your hands twice (making sure to keep your right hand offset slightly lower than your left as you clap, to show respect for man and the Gods not being as one) and then pray for something you wish. This properly awakens the deities so they may receive your prayer. When finished bow once and you may walk away.

When one reaches the altarpiece of the main hall in a Buddhist Temple, after making an offering, one need only light the incense or candle if there is one, ring the gong or bell if there is one present, bow and then press their hands together without clapping. Bow again once finished, facing the altar in all instances.

When exiting a Buddhist Temple or a Shinto Shrine, simply turn again to face the main entrance gate, bow once, and depart.

Remember the simple rule: Shinto Shrines are: Bow Twice, Clap Twice, Pray, Bow Once

Buddhist Temples are: Bow Once, Pray, Bow Once

Congratulations. You just mastered Buddhist Temples and Shinto Shrines in one go!